The ferrous oxalate route in the development of lithium iron phosphate (LFP) cathode materials has indeed experienced a dramatic journey of being replaced and then revived. Once the mainstream in the early industry, it was marginalized due to its own shortcomings and competition from emerging processes. However, in recent years, it has regained its footing in the high-end power battery market by leveraging its unique advantages in high compaction density and fast-charging performance.

The Era of Ferrous Oxalate Process Dominance

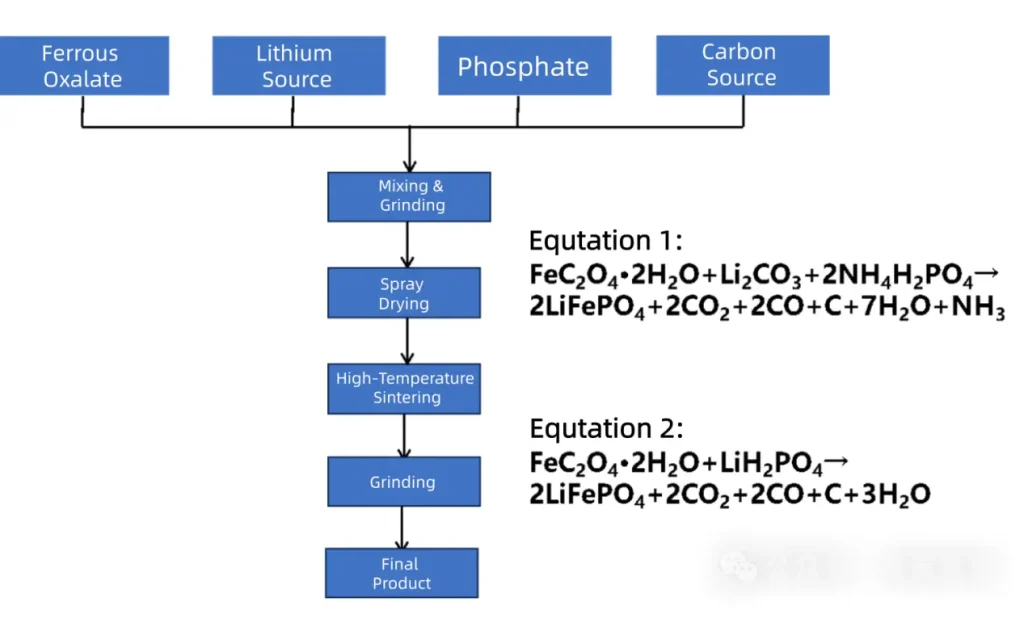

As early as 2017, the ferrous oxalate method was still the mainstream process for producing Lithium Iron Phosphate. The basic process route and general reaction equation are shown in Figure 1. Depending on the lithium and phosphorus sources used, the process involves two main reaction mechanisms (Equations 1 and 2), with the early process primarily following Equation 1.

The process route for producing Lithium Iron Phosphate using ferrous oxalate appears simple, but the key to product quality lies in the details of each stage.

1. Raw Material Selection and Control

The quality of ferrous oxalate is the fundamental core factor. High-purity ferrous oxalate powder with uniform particle size is preferred. The initial particle size of the raw material directly determines the particle size of the final product. Using spherical or near-spherical ferrous oxalate with a D50 of 2-3μm or even smaller can significantly improve reactivity and yield a product with high compaction density.

Traditionally, lithium carbonate was commonly used as the lithium source. In recent years, lithium dihydrogen phosphate has been increasingly adopted, as it provides both the lithium and phosphorus sources, making the reaction more direct. Secondly, its high reactivity and low decomposition temperature help lower the sintering temperature and improve product consistency.

Carbon sources are selected based on their ability to form a highly graphitized conductive carbon network upon decomposition, such as glucose, sucrose, and citric acid.

2. Calcination Process Control

This process typically employs a two-stage sintering method: the first stage involves low-temperature pre-sintering (~400°C) for sufficient decomposition of raw materials, and the second stage involves high-temperature crystallization (~600-750°C).

The pre-sintering stage mainly involves the decomposition of ferrous oxalate and phosphates: Ferrous oxalate loses its water of crystallization and decomposes into highly reactive ferrous oxide (FeO), releasing large amounts of CO and CO₂. The reducing gas CO forms a “protective shield” within the reaction system, effectively preventing the oxidation of Fe²⁺ to Fe³⁺ while also inhibiting excessive growth of the final product particles. When using ammonium dihydrogen phosphate as the phosphorus source, it decomposes during pre-sintering, releasing ammonia gas and phosphoric acid.

By controlling the pre-sintering temperature and time, lithium iron phosphate crystal precursors can be formed at relatively low temperatures. The released gases help remove impurities from the raw materials while inhibiting particle agglomeration and crystal growth, facilitating the production of LFP with high crystallinity, high purity, and uniform particles in the subsequent high-temperature calcination stage.

In the high-temperature zone, the highly reactive FeO comes into contact with the lithium and phosphorus sources, undergoing a solid-state reaction to form LFP crystal nuclei. Eventually, as the temperature increases and the holding time extends, these nuclei gradually grow, forming olivine-type Lithium Iron Phosphate with complete crystallinity and stable structure.

During the sintering process, the organic carbon source undergoes pyrolysis to form an amorphous carbon coating on the surface of the LFP particles, significantly enhancing the material’s electronic conductivity.

This process offered low iron source costs, relatively simple process flow, equipment investment, and operation/maintenance, making it the mainstream process in the early days of LFP synthesis technology.

Why Was the Ferrous Oxalate Route Replaced?

Between 2017 and 2022, the power battery industry experienced explosive growth. The demands for material consistency and environmental protection suddenly increased. In this context, the inherent weaknesses of the ferrous oxalate solid-phase method (poor consistency, difficulty in scaling up) were magnified. The iron phosphate route, with its excellent product consistency, more environmentally friendly production process, and overall performance better suited to the power battery demands at the time, quickly became the absolute market mainstream, at its peak occupying about 70% of the market share. In contrast, the share of the ferrous oxalate route gradually shrank to single digits.

Furthermore, the compaction density of LFP products produced by the early ferrous oxalate process was not yet high, leading to a widespread industry perception during this period that materials produced via the iron phosphate route could more easily achieve higher compaction density (≥2.4 g/cm³).

From equipment and environmental perspectives, the ferrous oxalate method produces CO and ammonia gas during sintering. CO is toxic and requires treatment. NH₃ is corrosive, severely corroding kilns and pipelines, thereby increasing equipment maintenance costs and time costs. In contrast, the gas products from the iron phosphate method’s sintering process are mainly water vapor, making waste gas treatment simpler, more friendly to production equipment, and resulting in lower environmental pressure.

In summary, the process replacement during this stage was a typical case of “industrial demand driving technological route iteration,” a result of market dynamics in a specific phase of development.

The Resurgence of the Ferrous Oxalate Route

The return of the ferrous oxalate route is not merely a repetition of the old process; rather, its core advantages have been reactivated under new market demands and technological advancements. After 2022, the popularity of new energy vehicles increased significantly, and “slow charging” became a core user experience pain point. Market demand for power batteries capable of “ultra-fast charging” (e.g., 400 km range in 10 minutes) surged.

Although its market share was once squeezed, the ferrous oxalate method was not completely abandoned by the market. As a precursor for LFP materials, it was the first to achieve breakthroughs in producing high-compaction-density LFP. Technological iterations overcame the early limitations of the ferrous oxalate process regarding product compaction, production safety, and production costs.

For instance, Fulin Precision Industry adopted serpentine tube reactors + electric heating delay reactors. Through precise temperature control, dispersant addition, and automated processes, they significantly improved product purity (≥99.5%) and particle size uniformity while reducing costs by 20%. Pengbo New Materials is also a leader in the domestic preparation of LFP via the ferrous oxalate method. Through special controls, they achieve an effective mix of large and small particles, filling the gaps between LFP particles to enhance compaction density. Combined with special metal ion doping, this results in LFP with very low powder resistivity. When applied in power batteries, it enables higher rates, meeting the increasing fast-charging demands of new energy vehicles.

Therefore, for LFP production processes to remain invincible in fierce competition, the related companies must closely follow market trends, root themselves in continuous technological innovation, base themselves on extreme cost control, and use the construction of a robust industrial ecosystem as their moat.